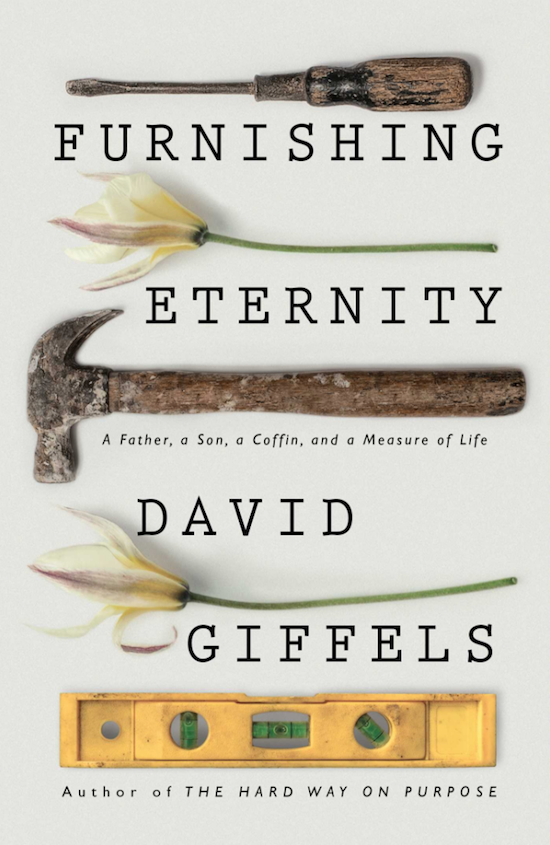

When David Giffels was 50 years old and completely healthy, he decided to build his own coffin with his 81-year-old, master craftsman father. Why? Well, I ask him that on today’s podcast. David Giffels is a writer who previously published a book of essays about growing up in the Rust Belt of Ohio in the 1970s. That title is called The Hard Way on Purpose. In his latest book, Furnishing Eternity: A Father, a Son, a Coffin, and a Measure of Life, he recounts the experience of building his own coffin with his father and the lessons about life, aging, and death that he picked up along the way.

We begin the show discussing why many in the Rust Belt live by the motto, “The Hard Way on Purpose,” and how it manifests itself in their undying loyalty to their sports teams that come up short year after year. We then shift gears and discuss David’s project of building his own casket with his dad, the expectations he had going into it, and why lying in your own coffin is, unfortunately, not as profound of an experience as you’d think it would be.

Show Highlights

- The character of the Rust Belt

- Ohio’s relationship with their losing sports teams

- The difference between losing and almost winning

- Why David decided to build his own coffin

- How the fates intervened in David’s exploration of mortality

- How the project changed after David’s mother and close friend died in short succession

- What’s it like to lose your parents and see them in decline

- Were any life lessons imparted by David’s dad during the building of the coffin?

- Why David didn’t get the epiphany he expected when lying down in his coffin

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Hard Way on Purpose

- Baker Mayfield’s impression of John Dorsey

- What Every Man Should Know About Losing a Loved One

- 5 Ancient Stoic Tactics for Modern Life

- Begin With the End in Mind

- On Losing Dad

- Boyhood

Connect With David

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Wrangler. Whether you ride a bike, a bronc, or a skateboard, Wrangler jeans are for you. Visit wrangler.com.

Starbucks Doubleshot. The refrigerated, energy coffee drink to get you from point A to point done. Available in six delicious flavors. Find it at your local convenience store.

Omigo. A revolutionary toilet seat that will let you finally say goodbye to toilet paper again. Get $100 off when you go to myomigo.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. When David Giffels was 50 years old, and completely healthy, he decided to build his own coffin with his 81-year-old master craftsman father. Why? I’ll ask him that on the podcast today.

David Giffels is a writer who previously published a book of essays about growing up in the Rust Belt of Ohio in the 1970s, called The Hard Way on Purpose. In his latest book, Furnishing Eternity: A Father, a Son, a Coffin, and a Measure of Life, he recounts the experience of building his own coffin with his father, and the lessons about life, aging, and death that he picked up along the way.

He’ll be on our show discussing why many in the Rust Belt live by the motto, “The hard way on purpose,” and how it manifests itself in their undying loyalty to their sports teams that come up short year after year. We then shift gears and discuss David’s project of building his own casket with his dad, the expectations he had going into it, and why lying in your own coffin is, unfortunately, not as profound an experience as you think it would be.

After the show is over, check out the show notes at aom.is/giffels.

David Giffels, welcome to the show.

David Giffels: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: All right. You wrote a book called Furnishing Eternity: A Father, a Son, a Coffin, and it’s all about you building your own coffin with your dad. But, before we get into that morbid story, let’s talk about your home state of Ohio, because you write a lot about that. It comes up in the book as well. Before this one, you wrote a collection of essays about the Rust Belt called The Hard Way on Purpose. I love the title of that. How does The Hard Way on Purpose describe the character of the Rust Belt in Ohio?

David Giffels: Yeah, I think it describes, especially for my generation, which is the people who came of age after the Boom years, after the glory of industry, and really only knew our hometowns as places that had fallen onto hard times, to commit to a place like Akron, Ohio, or Detroit, or Buffalo, or Des Moines was to make a conscious decision not to do things the easy way, or the glamorous way.

A lot of my friends from college moved to Chicago, because that was a Midwestern place that seemed like the easier way, on purpose. At first, it’s sort of a commitment to the grittiness and the struggle. But then, the on purpose part is that it just becomes your way of doing things, sort of. Like, I use an analogy in that book of Jack White from the White Stripes, who talked about when he was on stage, when he would have the stage set up. If the organ needed to be three feet away for him to reach it, he would have the stage crew put it four feet away, to create that sort of tension of the performance. I kind of think that’s a metaphor for the way we do things here. It would be much easier to root for the New England Patriots, but we love the Cleveland Browns.

Brett McKay: That comes up, too, the sports. I think everyone knows about Ohio and their love for their losing teams, for example, the Cleveland Browns. What do you think that says about … Is that, that hard way on purpose attitude?

David Giffels: Yeah.

Brett McKay: It’s like, “Things are bad, but we’re gritty. We’re going to stick through it no matter what.”

David Giffels: Yeah, but Brett, you said, “Our losing teams.” And it’s not that we lose. It’s that we always almost win.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

David Giffels: And that’s, you know, we’re like Charlie Brown, who just keeps believing that Lucy’s not going to pull the football away when he’s trying to kick it, because we just always have gotten so close. And in fact, when Lebron James came back and sort of delivered on his promise to bring a championship two years ago, there was a little bit, not just for me, but I think for a certain kind of person, a little bit of ambivalence. Like, we had the distinction of having gone 52 years, longer than any other pro sports city, without a championship. Anyone can win a championship, because everyone else had. But we had that one thing that we were like the long, still in the struggle. So, it was great when he won, but it was kind of an identity check. It’s kind of like, now that you’ve won a championship, you don’t really have that mantle of hard times.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I like that idea. You don’t lose, you just almost won, a lot. I mean, what do you think the difference between that … what’s the distinction there? Is it like there’s hope in the almost winning? Or there’s no hope in always losing?

David Giffels: Yeah. There’s a beautiful and terrible hope in that, because it’s not total despair, because there’s always that glimmer that we were just there. We were just on the goal line when we fumbled. Or we were just about to make the final out when it dribbled past the shortstop or whatever. That leads you to a kind of hope that’s not manifested by any truth so far, but you still believe it’s there. It’s a great human thing. That carries far beyond sports.

But it’s also a terrible thing, because you’ve never had proof that your hope will be fulfilled. But you keep at it. So, it’s a delicate line, but it’s one that seems to really be reinforced in so many parts of our culture. I mean, sports is just one example, but economically and culturally, so forth.

Brett McKay: Yeah, what I like about the distinction is, it sounds like, when you say, “We almost won,” instead of saying, “We lost,” it sort of, it gives you your sense of autonomy. It’s like, “We did everything we could, but we just came up short for whatever reason.”

Going back to sports, a lot of the reasons those teams came up short, it was just like a fluke. Right? A fumble, the ball bounced the wrong way. Wasn’t anything you could’ve done. And that happens a lot in life. And you did everything you can. Instead of saying, “Man, I’m a loser,” which is sort of like definitive and universal. It’s like, “Well, I almost won.” I don’t know, for some reason, yeah, like you said, it’s very hopeful.

David Giffels: Yeah, the older I get, the more I really think that the highest highs of my life and the lowest lows of my life are really more similar than different. The intensity of losing, or of almost winning, is very similar to the intensity of winning, or almost having lost. As opposed to the vast middle of what most of life is about. The day when nothing really happened isn’t the day you remember. Ten years later, you remember the death of somebody you love, or you remember your wedding day, in ways that are very similar. I guess I can handle losing more, because I define it as not winning, in every part of life.

Brett McKay: I got to ask you, because I’m an OU grad. Do you think Baker Mayfield is going to turn around the Cleveland Browns?

David Giffels: Well, of course I do. Just like I did with the other 30 quarterbacks in the last 15 years. But, what I like about him so far is that he has a sense of humor. And, if you live in Cleveland, you need to have a sense of humor. And the more bitter and twisted the sense of humor, the better. But, I don’t know if you’ve seen the video of him doing his imitation of John Dorsey, the Browns’ general manager?

Brett McKay: Yeah, yeah.

David Giffels: It’s hilarious. And it’s like born of a true spirit of humor. He’s going to need it, no matter what, for at least a couple years, he’s going to need that sense of humor. But, yeah, so far I like everything about him.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting. What do you think the humor is like in Ohio, thanks to … Particularly, I think Ohio gets a lot of attention, particularly during election years. And it’s sort of treated as a monolith. But it’s not, right? There’s southern Ohio, is sort of like Appalachia, almost. And then northern Ohio is something different. So, let’s say northern Ohio, where a lot of the industrial towns are. How is that … is there a sense of gallows humor there, you think?

David Giffels: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, it’s definitely the humor that comes from people who’ve been through a struggle, which has its own kind of edge to it. And, from a place that doesn’t have a lot of sunny days, and people sort of live with a kind of rye understanding of what it means to live in a kind of darkness.

But, especially because, for more than a generation, we’ve grown so used to being the punchline of other people’s jokes, so used to being misunderstood, or ignored, that we are very quick to get to the punchline quicker. And that’s a cultural thing. When you’ve been kind of laughed at, and you learn how to laugh at yourself better, and quicker, you diffuse somebody else’s attempt to do it.

Brett McKay: Right. I’ve seen that YouTube video about Cleveland. Like someone made a commercial about Cleveland.

David Giffels: Yeah, those are great. Yeah, the ironic Chamber of Commerce Cleveland, it’s not as bad as you think kind of vibe to it. Yeah. It’s awesome.

Brett McKay: Well, I think this kind of sense of gallows humor leads to a great segue to your new book Furnishing Eternity, which is about building your own coffin. Which I guess is something that someone who grew up in the Rust Belt watching, basically, the city decay and diminish. Something that person would do. I’m curious, what kick started this? Why did you decide I want to build my own coffin. Because you’re a young guy. How old were you when you decided to do this?

David Giffels: I was nearing 50, and it was not so much the press of mortality or sort of the big ideas of life. What really started out as was a sort of quasi-argument between my wife and me. We just celebrated our 30th anniversary, and when you’ve been married a long time, very often what sounds to other people like an argument between the couple is actually just us practicing our material. And so my wife comes from, she’s from a first generation Sicilian, very old school Sicilian Catholic mother and a father who was from the hills of Kentucky with very old traditional notions about most of life, including the way a funeral should be. Which is the sort of formal Catholic go to the funeral home, buy the manufactured Ethan Allen type piece of furniture and spend a lot of money on it. And that’s how things are done.

And I, in response to that, had this half-baked idea that I just wanted to be thrown into a dumpster after I die. And so I would exaggerate my side of it, and she would exaggerate her side of it when we would have this debate, especially in front of other people. To the point where it became like, “Well, I am never going to be buried in a $5000 piece of furniture. I want to be buried in a cardboard box.” And then she would … this would go on.

My dad was a master furniture builder and carpenter and made lots of furniture for us, and for my siblings and so forth. One night we’re having this debate, and I just looked at my dad and it was just really, literally just sort of a spontaneous, whimsical thing. I was like, “You know what, you and I could probably build a pretty cool casket together.” And it was like, immediately … because I’m a cheapskate too. I’m like it probably costs a couple hundred bucks. It would be one of those weird things that we like doing together. So really it was not any more than that than this sort of like just might be crazy enough to work idea that somehow took hold.

Brett McKay: Right so there was no like, yeah, existential memento mori thing. You didn’t think this would be a great book. You’re just like, “No, I’m going to build a coffin because my wife thinks that’s dumb. Let’s do it.”

David Giffels: Yeah, well here’s where it gets weird. Here’s where fate comes in. Because you’re right, it wasn’t initially. But very soon I’m like, “You know, I think I would like to write about this.” And then I’m like, you know, I’m getting to that point in my life as a person and as a writer where the big ideas are important. And this could be my death book. I could sort of philosophically, esoterically think about the notions of mortality and death. But I hadn’t lost anybody very, very close to me really in my life yet. Both my parents were still living. I hadn’t really had this sort of unexpected death of somebody at an age that seemed to be young. So close to me that it had really kind of hit, sort of punched right in the stomach. So I’m like, “Yeah, so I’m going to use the template of this narrative of my dad and I doing this project together as a way to explore one of the big themes that writers should take on.” And, “Ha, ha, ha,” the writing gods said.

Within a year, my mom unexpectedly died. She had been struggling with cancer but she had a heart attack and it just kind of took her right down. And then a year later while we’re still in this project, my best friend, who was my age, too young to die, not even 50, also died. So, it was kind of like the writing gods said, “Oh, you want to dabble with the mortality theme do you? Here you go.” So it really, I mean, it changed everything completely. It changed the book completely, and it changed my life completely. And kind of taught me a very humbling lesson about how to think about things and the actual lack of agency that writers have when we believe we have sometimes complete agency.

Brett McKay: How did losing your mother and your friend so close together, and while you were doing this project of building your own coffin, how did that change the project? When you were working on the coffin did it take on significant? Like, was it more heavy on you?

David Giffels: Yeah, absolutely. First of all, because I was actively writing the book when that happened, and this was a different kind of book. It was more like, it’s a memoir, but it was really more journalistic. Because I was documenting the process of building this thing as it was happening. So when these events unexpectedly come in, I had to deal with them in a practical way as a writer. And so first when my mom died, I’m actively grieving her, and trying to make sense of it. The chaos of grief, grief is violent and moves in cycles that are hard to understand. And to try to gather that as a writer and make sense of it on the page was a huge challenge. And then a year later to go through it again with my friend. So, logistically it was troubling.

Yeah, so then going back to my dad’s … my dad’s workshop was in his barn out in the country in a suburban township near Akron, Ohio where I live. So, I’d make these treks out to his barn and work there, sometimes alone. I found it to be therapeutic because even though I’m obviously building my own coffin, which seems like a sort of overt connection with the death and the temporal nature of life. It was really just a process that I could put my hands on and understand in a much more concrete, tangible way than trying to understand the concept of that my mom wasn’t there to ask a question of or that my friend John wasn’t there to say let’s go see a band. It was a weirdly, a kind of a comfort just because it was something that I could work on.

And also work on with my dad who suddenly became hyper-aware. Dad is 83 years old. He’s the oldest person I know. Like constantly thinking, am I going to get the phone call that he’s … something suddenly happen to him. So, just to spend time with him where it wasn’t about thinking of his mortality, but just this thing we were working on was helpful.

Brett McKay: Well, and he developed lung cancer during this thing as well, right?

David Giffels: Yeah. He sort of tricked me. Because he actually, yeah, just as we got the idea that we were going to do this project, he was diagnosed with cancer. And he had to undergo treatment. And it was pretty heinous treatment. They basically just put him in this, looked like the man in the iron mask contraption that they would strap him down on this thing. And just blast the … out of it with radiation. He would come home and he just go to work in his garden from each day’s treatment. He really deliberately tried to make this not be what his life was about. And by virtue of that it made me think, “Well you know, I’m sure cancer’s bad, but look dad’s so tough. Look how he’s doing it.” And so for about the five years that this project spanned he was being treated in some way or another for cancer. But proving that you can live a vibrant life without it.

I mean, I mentioned before that I thought of him as the oldest person I knew. And especially after my mom died, and I saw the way he dealt with it. He also seemed like the most alive person I knew. He never talked about it but you could just sort of see by the way he was living that he was going to make the very most of the time and energy that he had. And so he really lived … I mean, it’s cliché but he lived life to the fullest in the final years of his life. And I should point out, the book ends with us sort of finishing this process. And then it takes about a year for a book to come out after the time the manuscript’s been accepted. This book came out on January 2nd, three day later my dad died. So it was kind of … Yeah, thanks.

It was definitely the strangest irony of my life, and probably of his life. But in a way, I was really glad that we had done this. Really glad that he had gotten to see what the book was, and to get to understand it. Again, it’s kind of like, this book has had a weird life of its own from the very beginning. Taught me a lot more than I ever could have guessed it would.

Brett McKay: I know there’s a lot of our listeners who are probably your age in their 50s. That’s kind of a weird time. If your parents are still alive, they’re in their 80s probably, they’re getting sick, and then you finally … I mean, what’s that like seeing your parents slowly decline? And then finally, and then what’s it like when you no longer have parents? Did you feel something different? I remember when my mom when my grandfather died not too long ago. She’s finally says, I finally … it’s weird not having parents on earth. It’s like, I feel like an adult. Like fully an adult almost.

David Giffels: Yeah, I think specifically as sort of a Generation X-er there’s something about the way we view aging and mortality that’s unique to our generation which is that, like I don’t really know what age I am. I mean, 50 is a weird number to me because it doesn’t seem like what 50 probably used to be. I don’t know if that’s true, but it certainly seems true. It just seems like in an age of cultural acceleration that I don’t feel a generation gap from my kids. But it’s not like I’m trying to act like them or trying to be younger than I am, but I also don’t feel embarrassed that I am interested in new music when I was supposed to leave that behind at age 30 or something like that. And so by the same token, my wife and I have talked about this. We’re like, it just seems like we made this invisible leap from going to all of our friends’ weddings to now going to their parents’ funerals.

There is just this sort of generational thing that kind of slips in, in a sneaky way that all of a sudden it’s kind like our parents our dying, we don’t really know what that means. So, for me to lose my mom, it was a confrontation with mortality that I hadn’t experienced before. But it was really confounding. It was hard to put into context because I started thinking of myself … After she died one of the things that starts happening, happened with me and I’ve heard other people say this, is you start to do sort of obsessive math. At first, it’s like it’s been exactly three days since I spoke to her. And then it’s been exactly two weeks and one day since she was in our house, and she was standing on that floorboard that’s three floorboards away from the base board or whatever. But then I started to do in my head I would calculate who she was at exactly the age I am now. If I was 48 years, three months, and six days I would actually try to figure out, okay that was this year and I was let’s say like who was she in relation to my dad.

Brett McKay: No yeah, I know exactly.

David Giffels: Do you know what I mean?

Brett McKay: Because after I read that I started doing that with my parents. My parents were both still alive but it’s like, yeah, what were my parents like when I was … What year was it when my parents were 36 years old?

David Giffels: Yeah. And when my dad turned, 50 did he feel like he was becoming an old man? Because when I turned 50, I didn’t have … it was just like, I don’t know. I went for a run and I probably listened to Parquet Courts or something. And I don’t know, it’s just-

Brett McKay: Yeah you don’t start listening to Bobby Darin-

David Giffels: It seems different.

Brett McKay: Frank Sinatra.

David Giffels: Right, yeah, exactly. Band music, you know.

Brett McKay: It is weird. I’ve heard that from other people too like in the Gen X generation. They’ll say like, “I feel like I’m 18, but when I look in the mirror I see this 50-year-old guy. And it spooks me sometimes.”

David Giffels: Yeah. Yeah. Am I allowed to wear skinny jeans?

Brett McKay: Can I still wear Converse? Is that okay?

David Giffels: Yeah. Several years ago, Redbook Magazine did it was like how men think issue or something. And they reached out to a whole bunch of writers and celebrities, and asked them all to write little pieces. So they contacted me and they said, “We want you to write a piece for this. We want you to write a piece, why are men obsessed with being cool.” And I’m like, “Oh this is awesome.” And then they said, “You have 200 words.” I’m like, no. It would be easier for me to write 20,000 words on that subject. Because, especially now, it’s not out of the question for somebody in their 50s to still be hip. But if you’re trying, you’re failing. So, yeah it’s so different, I don’t know, it’s a different kind of generational crisis I think.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s weird. Yeah, and I think you’re right. It’s that acceleration of culture. Everything seems super compressed. I’ve thought about that too. When I’m in the car with my kids and they’re enjoying the same music that I’m listening to. Which never would have happened with my parents. My dad had Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass albums. I’m listening to them now, because I inherited them, I think it’s pretty cool. But when you’re 12 you’re like, “Boy, that’s pretty lame.” But, my kids they enjoy the same … They enjoy The Killers, they enjoy Bleachers, they enjoy the same music that I like to listen to.

David Giffels: Yeah, yeah. I was listening to Kendrick Lamar. They didn’t know what to make of it. It was like, “Do we need to go find some other music now so that we’re not listening to the same music as you?” I’m like, “No, it’s interesting. I’m sure it’s interesting to me for different reasons than it’s interesting to you,” is what I said to them. And I think that helped.

Brett McKay: Yeah that saved Kendrick Lamar for them. Well, let’s go back-

David Giffels: Right. Yeah, so we have that.

Brett McKay: … to working on this with your dad. And that’s a great set up for the stereotypical father/son working on this project together. You know, like a river type through it type thing where fatherly wisdom is imparted and et cetera, et cetera. Did that happen? When you started working on this with your dad were you hoping that you would gain all the wisdom that he had while you were sanding your own coffin?

David Giffels: Of course, I was hoping that, but I knew my dad well enough to know that that’s not exactly what would happen. Anytime that I would try to get philosophical or feelsie about it he would make a rye joke out of everything. Going back to my earliest memory, my favorite times with my dad were always when I was with him either in his workshop or when he was working on a project somewhere around the house. Because he was always doing that. He was an engineer and a really inventive tinkerer. And a really talented worker, and just good with all of the things that a household needs and all that. And I always just really loved either just being around him when he was doing it or actually helping him with that. And I took on a lot of that interest too.

And so kind of our best bonding moments, for lack of a better term, have been in those kinds of projects. Where it wasn’t like we had to talk about, “Isn’t this great that we’re doing this together? Thanks for being my dad.” It was never like that. It was just like, we just both enjoyed doing it together. And we both gathered by us mostly just certain things from each other.

So this was pretty early on in the process, he knew that I was going to be writing about this. In fact, I actively sometimes as we were working in the dusty workshop I’d go over to my notebook and write something down. And he’d be aware of it. Sometimes I’d ask him to say something again because I wanted to make sure I wrote it down. And so he just kind of chuckle and he just nod. Basically he just went along with it because he was a good sport. But, did I do it specifically to get some new experience from him? Again, I had some hope that there would be something special that would come from it, but really just what came from it was I created some new extra time with him that we got to spend together solely, the two of us. And then, upon his death, I immediately was so thankful for that.

Because at times I was like, I hope I’m not wasting his time. Or I hope he’s not wishing he didn’t have this. It ended up taking us four years because we kept getting busy with other things. We’d come back to it, and it was taking up room in his workshop. And I’m like, “Am I being a burden to him?” But as soon as he passed, I was like, “No, I’m glad we did that.” And I’m sure he was too.

Brett McKay: Yeah. I love that how … You had that hope that you’d get some sort of wisdom, but you didn’t, but it was still worthwhile. I feel like a lot of young people, I don’t know, parents, that are like in their 30s, 40s, they put high expectations on themselves. On like what it means to be a dad, and they should always be imparting this important wisdom to their kids at any moment. But I remember when growing up, my dad wasn’t like that. He wasn’t the talkative type. But the best memories I had of him was when … My dad was a game warden. And sometimes he would take me out with him patrolling, checking duck hunters. And that was just awesome. I got to get up at 4 o’clock in the morning. I was in the truck with him for hours. And we didn’t really talk. But it was great. I loved it. For me that was sufficient. Sometimes I’ve tried to remember that with my own kids. I don’t need to always be lecturing them, imparting, hoping to stuff their heads with as much knowledge, and just being there is enough.

David Giffels: Yeah. You know, as my kids got older, because I was the same way. I was definitely more emotive in the household than my dad ever was. Like I refer in the book jokingly to myself, is the emo mascot of the homestead. But you wonder, did I say enough? Or did I give them enough examples? My kids are college age now. I see enough of how they’re living their lives now to think, yeah they were probably getting what I was hoping or some of what I was hoping they would get. But, yeah kind of to that overt imparting of wisdom or bonding or whatever, there is a unexpectedly funny moment that happened that I read about in the book.

You know the move Boyhood? The Richard Linklater movie? When that came out, I got the DVD and I was like … My dad always came over on Sunday for dinner. So, I’m like, “Dad, why don’t you come over early in the afternoon. And you and my son, Evan,” who was exactly the same age as the boy in the movie, “And I will watch this movie together.” And so we sat down on the couch. I was all, like, “I like this, this is going to be great.” It’s going to be three generations of men watching this movie about two generations of father and son sort of aging in real-time before us on age. It’s going to be like this really meta, emotional experience. And 10 minutes into the movie, I’m sitting in the middle, and they’re both kind of starting to fidget. And this is like a three hour movie. So it was like this long afternoon of me hoping for something meaningful to happen to both of them. Kind of like, okay, is this going to go over?

In the movie you see the … if you know the way it was filmed, the characters age in real time because Richard Linklater came back every year I think and filmed a new set of scenes. So this movie you see the characters age in real time. And I felt like we watching it were aging in real time as we were viewing the movie.

Brett McKay: Yeah so okay. I guess insight there’s don’t put so much pressure on yourself as a dad.

David Giffels: Exactly, exactly.

Brett McKay: It made me think about a great example of not putting pressure and just enjoying the moment is that a Field of Dreams, the end, where Kevin Costner plays catch with his ghost dad. Right? They’re just playing catch. I’m sure they didn’t talk at all. They just threw the ball.

David Giffels: Right. Yeah. As you might expect, when one builds his own coffin, one knows that there will be some point when he or she will have to lie down in it. I mean, you got to take it for a test drive, right? And os I was aware of that as we were going through this that there would be some moment when that would happen. And I’m like, “I need to time this right. Because it’s going to be the most meaningful moment of this whole process.” I want to know what it feels like to lie in my final resting place. All of this pressure. And when it finally happened it’s like … really was one of these like, “Okay, let’s get this over with” moments. And I laid down and I’m like, “Okay, let’s feel it.” And it’s kind of like, “You know what, death is really not interested in me.” Death has bigger fish to fry.

You hope for those epiphanies in your life, and there’s certain moments in your life when you expect them. The truth is life is indifferent. And we are so, so small and so temporary that we’re not as big as we think we are. We’re not as worthy of lightning bolts coming into our bedrooms and revealing things. It’s much more of a main thing.

Brett McKay: And that’s why, I mean, although it’s crazy, it’s like you should be … that’s what makes those experiences when you do have them. When you’re not expecting, which makes them all the more meaningful. Because you weren’t expecting it, and it sticks with you the rest of your life.

David Giffels: Yeah.

Brett McKay: All right, so we’ve been really heavy and philosophical. Let’s get to the brass tacks of building a coffin. Reading this, I learned a lot about coffins that I didn’t know about. For example, there are dimensions coffins have to be in order for you to get it in the ground. And if you go too big, then you’re going to have to spend thousands of dollars extra to accommodate that. What are the dimensions of a … Was the coffin smaller than you thought it was going to be?

David Giffels: It could have been. It started to expand without our realization. As good an engineer and designer as my dad was, yeah we knew the dimensions. I can’t tell you offhand what they are, but they’re in the book. I consulted with a funeral director as we were working on this. He told me what the standard dimensions are. And when you’re talking about like a traditional burial situation, the dimensions are limited to the size of the vault that the casket has to go in. And it’s usually concrete or metal. And the reason for the vault is so there won’t be a sinkhole where the grave is. It’ll keep it from just collapsing after the organic materials break down. Which is what they really should do. Yeah, so if it exceeds the dimensions of a standard vault then you have to either buy a really expensive mega vault or something, or accommodate it some other way.

And so, anyway, because we kept coming up with other ideas to expand on the design of this thing, we somehow accidentally made it bigger than the standard vault. And I don’t want to give away too much of the drama of this situation, but we had to figure out a way to deal with that situation. So yeah, there were some practical considerations, definitely . . .

Brett McKay: And yeah, coffins are expensive, and they can get really elaborate. I think there’s coffins you can buy with your sports team emblazoned on it.

David Giffels: Oh yeah. You know, the weirdest thing, Brett, was when I was researching this and just kind of like free form … doing some Google research early on. I was just like struck by how immediately available a casket is. Because it’s something you never think about. And so suddenly you have to think about it. You can get a casket from Amazon with overnight shipping. And you can buy one from Overstock, you can buy them from Walmart, eBay has listings, which was weird. Because the eBay listings all use sort of the standard eBay language. So it’s like, unisex casket, one size. And overnight shipping available. But then it would also say, new. And I’d be like, “New, as opposed to used?” Yeah, so that was weird. But the weirdest was … Yeah, then all these novelty caskets.

And I discovered there’s a company that makes a bacon casket, and it’s a steel casket but it’s encased in bacon. And it has these options like you can get a bacon air freshener for the inside, and the marketing copy said for when you get that buried underground, not so fresh feeling. Yeah, some really weird ones. But, if you can make people laugh at your funeral that’s a good thing.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s very Egyptian. When I read that I was like, “That’s like something an Egyptian king would do. I want to be buried with bacon so that I can eat bacon on my journey to the …

David Giffels: Yeah, exactly.

Brett McKay: Right, cool-

David Giffels: A cool Egyptian king.

Brett McKay: … a cool Egyptian king.

David Giffels: For sure.

Brett McKay: And then there’s also, you can just get a cardboard box now and be buried in it. I guess it’s greener, eco-friendly.

David Giffels: Yeah. I got really interested. Green burial is really, really growing. And I got really interested in that. My Sicilian, Catholic wife will never probably go for that because we have to buried near our family members, because somehow we’ll be having parties there in the cemetery. But I really would love the idea of being buried in one of these organic cemeteries where you’re basically … I mean, the ones that I am familiar with, you’re put into the ground with the minimum of covering. You can just be wrapped in cotton. Everything has to be biodegradable. You could put a marker there but it can’t be a polished stone. They want it to be a natural stone. And they like that because it provides habitat for salamanders and things. And there’s something about that, that strikes me as the way maybe we should be doing things.

I’m Catholic, and so I know what my traditions are. But even cremation was not a Catholic thing until very recently, and now it’s a huge growing trend. There’s something just practical about the organic possibilities of burial. But I think, also, sort of spiritual about it. Shouldn’t I be, A, creating as little disruption and damage to the environment when I’m no longer part of it. And B, sort of recognizing that I’m not … What’s the point of preserving the box that I’m buried in with a concrete vault when I’m going to be decomposed in a week?

Brett McKay: Dust thou art, and to dust shalt thou return. Right. Let’s get building there.

David Giffels: Yeah. Yeah.

Brett McKay: Within a big metal box. What is it, I wonder what decomposing is like? Does he turn into dust or is it sort of like a leak? That’s another thing people don’t know about coffins, you have to put in pans in the coffin because bodies leak whenever you’re buried.

David Giffels: Yeah. Yeah, one of the hilarious things when my dad and I were going through this, we’d go to the hardware store, or the lumber yard. We’d be picking materials and he’d be like, “What I’d really like to do cedar or redwood because they’re less resistant to rot. And I’m like, “Dad, I’m not resistant to rot, so like what’s the point?” He’s very practical but I point these things out and then he’d laugh. But, yeah it was …

Brett McKay: So coffins are big. You’re not dead yet, so you’re not using it. So, what are you doing with your coffin right now?

David Giffels: Yeah, so like I feel like I’m giving away all the spoilers.

Brett McKay: I know, well, you know what you just-

David Giffels: So anybody listening, you really don’t need to buy the book. Because, yeah, I’m telling you all the good stuff. At one point when we were doing this, well first of all, there was always this question between me and my wife. Where are we going to store this thing? And I would always just sort of bluff and say, “Oh don’t worry, I’ve got a plan.” Which, most men when they say, “I have a plan,” mean I’ve got no plan. But at one point we had to stand it up on end in my dad’s workshop to make some room for something. When I looked at it I’m like, “Wow dad, you know what? That would make a really cool, nice bookcase.” And so that idea took hold. I made a set of, eventually, removable shelves that insert into the standing up on end, rectangular piece of furniture. It’s sort of an elegant solution.

The only problem is that when I started to figure out where in our house this thing would fit. The only place that it would work, based on the way the house is laid out and where furniture all ready is and so forth, is on the second floor of our house where the bedrooms are there’s a big, open, central hallway. And so, there was a perfect spot for it in that hallway. The only problem is that when my wife and I get up in the morning the first thing we see when we open up our bedroom door is the casket. And which I will be buried some day. Which would seem on the surface to be kind of a morbid thing. But when I think about it, if you wake up in the morning and the first thing you realize is that I will die someday it sort of puts you on your game for the day. It’s kind of like, yeah, let’s get coffee and get busy.

So, the other thing is when the book launch happened it was at Akron’s main library, has an auditorium and that’s where the book launch event took place. And the library staff made these … They reserved the first two rows of seats for my family and some guests. They made these laminated cards that have my author headshot and it said, “Reserved for a special guest.” And my wife brought one of those home and she has attached it to the side of the coffin. So it’s my picture reserved for a special guest on the side of my casket.

Brett McKay: Yeah, David, this has been a good conversation. Is there anywhere people can go to learn more about your work?

David Giffels: Yeah. I have a website, it’s davidgiffels.com.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. Thanks for coming on. It’s been a good conversation.

David Giffels: Oh, thanks so much for having me. This was a great conversation.

Brett McKay: My guest today was David Giffels. He’s the author of the book Furnishing Eternity. It’s available on Amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. You find out more information about his work at davidgiffels.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/giffels, where you find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness Website at artofmanliness.com. And if you enjoyed the show, you got something out of it I’d appreciate you give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that all ready, thank you. Please consider sharing this show with a friend or family member who you think would get something out of it. As always, thank you for your continued support. And until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.